Rulers in the Neo-Sumerian age and Egypt’s Old Kingdom utilized statues to convey a message of power, wealth and divine connection to their deities. Gudea of Lagash used statues in his own image during his rule in the Neo-Sumerian age to show his wealth and connection to his gods. The pharaohs of Egypt’s Old Kingdom used a larger number of statues that showed their power and they had an even greater purpose in Egyptian religion. Though the meaning and usage of statues varied for these rulers, they both used statues in their religion and chose materials that would show their wealth and desire for immortality.

Gudea was the ruler of Lagash during the Neo-Sumerian age in approximately 2100 BCE. He wasn’t born into royalty but he married the daughter of the ruler at the time, which secured his position in the royal house of Lagash. He was an extremely religious ruler and continually made gestures and gifts to various Sumer gods throughout his rule. He believed that the gods sent him dreams and visions as a means to communicate with him, which he interpreted as a message from the gods to erect temples in their honor. He went on to create and restore many temples throughout Lagash and upon completion of each temple he would place a statue made in his own image within. These statues where meant to be a representation of him within temple, always praying with his eyes focused on the gods. It is through these statues that survived from his age that we are now able to learn of his dreams, temples and religions beliefs through inscriptions carved into each one. Though his chosen title was that of ensi, the ruler, he referred to himself through these statues as “god of Lagash.” One of these inscriptions tells us of a great holiday celebration that lasted for seven days after the statue had been installed. There are over twenty four statues of Gudea which, either standing or sitting, always have his hands held together at his chest in prayer, have him dressed in the same clothing with one shoulder exposed, and range in size from about a foot tall to just over five feet. His head is either left bald or capped with a round wool lined hat. The gowns he was depicted in were covered with inscriptions with either messages to the gods or detailed explanations of why he was positioned in that particular fashion, with his chest showing him full of life and more defined arms showing the strength granted to him by the gods.

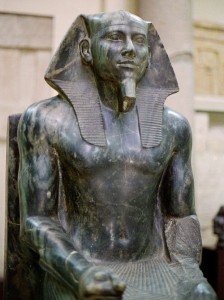

Seating diorite statue of Gudea, prince of Lagash, dedicated to the god Ningishzida, neo-Sumerian period.

The statues of Gudea were made from a highly polished dark grey stone called diorite, it is this material that gives these statues a very strong presence within the space and conveys their importance. Diorite wasn’t local to Lagash and had to be imported. It was such a highly prized material that early Mesopotamians listed it as a reason for conducting military expeditions. Gudea displayed his wealth as a ruler with this choice of material and the prestige of diorite was transferred to the statues that were carved from it. An inscription on one of the statues of him reads, “This statue has not been made from silver nor from lapis lazuli, nor from copper nor from lead, nor yet from bronze; it is made of diorite.” In all the statues he had made in his image, he can be seen wearing the same ceremonial clothing and is holding his hands together in prayer, as a permanent display in each temple showing his servitude to his gods. In each statue there is an inscription, which either speaks of his building of temples, service to the gods and of the gifts of wealth and health bestowed by the gods to him and his land. In one particular statue of him, in which he is seated, a blueprint for the construction of the temple E-ninnu is placed on his lap. This temple was dedicated to Ningirsu, the god of war, who was one of the gods giving him visions and when it came time to build this temple he took a very hands on approach. He first measured the site where the temple was to be built and during a festive celebration he laid the first brick. He attributed his visions, dreams and wealth to his divine connection with the gods. His choice of materials for his statues, installing them into temples built for the gods and the form the statues take, all served to elevate him to a status above all others in the eyes of the gods.

Nearly six hundred years earlier in Egypt’s Old Kingdom, around 2700 BCE, the pharaohs were also having statues constructed but with a very different purpose in mind. Pharaohs had these statues placed with them in their burial chambers as an alternate home for their ka, their life force, after they died. Since mummification during the Old Kingdom wasn’t as refined as it later became, these statues were vital to the pharaoh’s afterlife if their body was destroyed for any reason. During the Fourth Dynasty, the pharaoh Khafre, had statues made with many common characteristics that can be seen in the statues of other pharaohs during the Old Kingdom of Egypt. One of the most famous statues of Khafre was sculpted from diorite and had the same highly polished, deep dark grey characteristics as those that can be seen in the statues of Gudea. The form of the pharaoh is that of an idealized shape, perfect in physique, definition of muscle and imposing size, all of which make up what a pharaoh should look like. The pharaoh can be seen sitting erect on his throne, wearing a simple kilt. His eyes are looking straight out into the distance with his arms at rest on his thighs and his legs are parallel to each other and perpendicular to his body. This position gives the appearance of an alertness and calmness that would remain eternal. The throne in which he is seated has arms and legs are shaped to look like the bodies of two lions and papyrus plant reliefs fill the spaces between the thrones legs. Horus, the falcon-god, sits atop the thrones back with his wings out to either side of the pharaoh’s head as a display of his protection. This statue of the pharaoh Khafre displays him wearing a headdress and false beard making this a very iconic royal statue. Khafre’s back and legs are attached to his throne and the rigidity of his posture and lack of an extending parts was done with the intent to convey the desire for an existence throughout the rest of time. Another common position statues of the pharaoh’s were carved into was that of standing in mid-step, one particular such funerary statue is that of the pharaoh Menkaure and his wife Khamerernebty. They were carved in a manner to reflect an idealized physique similar to that of the Khafre statue. They stand together with their backs still attached to the stone from which they were carved. Khamerernebty’s right arm is holding the pharaoh’s waist and her other left hand rests on his arm which is typical of Egyptian sculpture to signify they were married. Other than this contact, there is no other emotion displayed in the statue, they both look straight into the distance and stand as a permanent sanctuary for their ka. Several apprentices, each apprentice working in from one side, crafted the rough form of these particular funerary statues from a single block of stone. Once the rough form of the statue had been achieved, a master sculptor came in to complete the work.

There were many statues sculpted for each pharaoh, his wife, priests and other servants to help serve him in the afterlife, these statues also served as a means to help the pharaoh become more connected with the gods. The serdab, meaning the “house of the statue”, was the main resting place for these statues which were also used in a couple of rituals, the most important of which was the opening of the mouth ceremony. In this ceremony, priests would magically open the mouths of the mummy and a statue in order to allow the pharaoh the ability to speak and eat in the afterlife. This was a very long and well-documented ritual in which a new statue of the pharaoh was carved and dressed in order to give the pharaoh back the use of his mouth. The statues were also the primary focus of the daily ritual performed by priests. They preformed this ritual by cleaning the statue with water before applying ointments or oils. They then dressed the statue and applied makeup to it as a means of preparation for other rituals to come. The rituals that followed included offerings of food for the pharaoh and then ended with the cleansing and purifying of the temple. These statues and rituals were a significant part of life during Egypt’s Old Kingdom. The pharaoh’s used many different materials for their statues but Khafre, like Gudea, wanted to use diorite for his statue. He knew that diorite was a valuable, tough and beautiful material that would give his ka an immortal place to reside after he passed. The diorite for his statues had to be mined from quarries about 400 miles to the south before it journeyed north to be sculpted. The quantity of statues carved, their choice of materials and the rituals surrounding them proved just how significant the pharaoh’s commitment was to the gods and to success in the afterlife.

Through their personal and spiritual connection with their statues the pharaohs regarded them much higher than Gudea of Lagesh did some 600 years later. The pharaoh’s statue was to be the eternal resting place for his ka after death and while the sheer number and choice of materials for the statues displayed the pharaoh’s great wealth, their ultimate goal was achieving a divine afterlife in the company of the gods. Gudea of Lagesh, while connecting his statues to divine communications and visions from the gods of Sumer, put more emphasis on the statues as a means to display of his power, wealth and status above all others. While Gudea used the statues and their surrounding temples to influence his people during the Neo-Sumerian age, for the pharaoh’s these statues were the ultimate vessels for their life force that would allow them to live as a god among the gods for all eternity. Both rulers, while hundreds of years apart, used statues to depict their power and the significance of their religious beliefs. The rulers’ choices of durable materials, importance placed on their beliefs of life and afterlife, and reverences placed on their statues truly have enabled them to far outlive their kingdoms and earthly bodies.

References

Gardner’s Art through the Ages: A Global History, Volume I

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diorite

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Statues_of_Gudea

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gudea

http://www.third-millennium-library.com/readinghall/GalleryofHistory/Ancient-People/GUDEA.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gudea_cylinders

http://www.reshafim.org.il/ad/egypt/portraiture/index.html

http://www.reshafim.org.il/ad/egypt/funerary_practices/funerary_objects.htm#statues

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ka_statue

http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/religion/wpr.html

http://www.philae.nu/akhet/OpenMouth.html